Opinion piece by Paul Callister and Robert McLachlan first published by Greater Auckland on 22 September 2021 concerning increase road traffic on the Kāpiti Coast between Wellington and Levin due to upgrading on State Highway 1 to a 4 lane road corridor. Republished on publictransportforum.nz with permission from the authors.

The challenges of decarbonising Auckland’s transport are significant. But are other regions also playing their part? The Kāpiti Coast and Horowhenua region illustrates the challenges when declarations of climate emergencies do not lead to real action, and a silo mentality to transport and urban planning takes us down the wrong path.

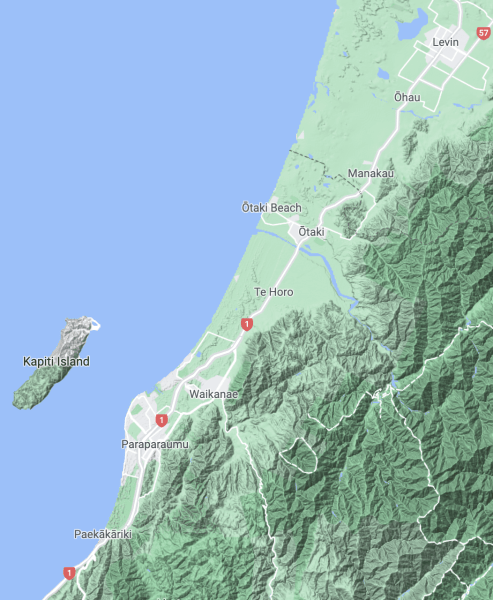

Anyone travelling from Wellington to Ōtaki in the last couple of years would be struck by the massive amount of road construction taking place. At a time when we know we need to dramatically reduce transport emissions, motorways have absorbed much of the region’s transport spend.

The largest project is Transmission Gully which is expected to cost $1.25 billion directly and $3 billion during its run of private operation. In Kāpiti, this connects to the Mackays to Peka Peka expressway ($630 million). Still being constructed is the Peka Peka to Ōtaki expressway ($405 million).

These projects were set in place before the government declared a climate emergency. Yet, despite this declaration both National and Labour support the Ōtaki to Levin motorway extension. The estimated cost was originally $817 million which gave a very low benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 0.22-0.37. Already there is talk of a cost blowout

to $1.5 billion. On this basis, the Ministry of Transport and Treasury advised against the project, but were overruled by cabinet.

BCR is the ratio of the present value of the benefits of a project to its costs. Prior to July 2009, it was the main method for determining which projects went ahead. Then it became just one component of several, with the project’s ‘strategic fit’ allowing projects with low BCR to be built. Average BCRs of new roads fell from 4

to 2 by 2010, and are now routinely less than 1. That is, they trigger an immediate net loss to the economy. Michael Pickford, in a 2013 review of the change, pointed out that the true loss is even greater as projects with higher benefits are foregone. He concluded that there were serious doubts about the rationality of the

decision-making process. In a climate emergency, sticking to previous irrational decisions simply demonstrates an incoherent lack of resilience in processes.

In contrast, spending on rail has been small. The main project, completed in 2011, was double tracking and electrification from Paraparaumu to Waikanae at a cost of $14 million.

Traffic increases in direct proportion to highway construction, a finding so well established it has been known as the “Fundamental Law of Highway Congestion” for sixty years and verified all over the world. There is no reason to think the Wellington region will be any different, especially the 45 km stretch from Levin to Paraparaumu that has prime potential for linear sprawl.

The Horowhenua and Kāpiti communities

Kāpiti is a series of coastal villages with a mix of high- and low-income areas. Waikanae in particular has been seen as an area for retirement and consequently has an older population. Like all areas of New Zealand there are housing shortages.

Horowhenua, whose main centre is Levin, begins north of Ōtaki. It has the second-lowest median income of New Zealand’s 66 territorial authorities. Now it has a housing affordability crisis as well, as median house prices have risen from $195,000 in 2016 to $530,000 today.

All the towns along the Kāpiti Coast and Horowhenua were historically developed around railway stations on the main trunk line. This means almost all of the existing urban development is within easy cycling distance of these stations. Using Google Maps, examples are Paraparaumu Beach to the station is estimated to take 15 minutes by

bike. Waikanae Beach to that station is a little longer at 19 minutes. Otaki Beach to the station is 16 minutes. And most areas of the current Levin township are 10 to 15 minutes cycling to that station.

Car dependency

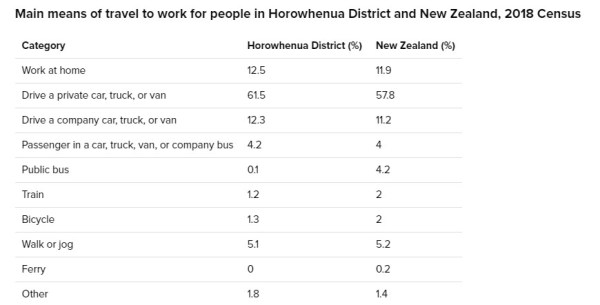

Like most of New Zealand, both Kāpiti and the Horowhenua are very car dependent. This shows up in greenhouse gas emissions and in transport surveys.

Given the lack of public transport, people living in Horowhenua are especially reliant on cars. Some of these commuters will be working locally but Palmerston North also provides employment. A small but growing group will go as far as Wellington. Despite Levin being flat, compact and with relatively wide streets, rates of cycling to work are very low.

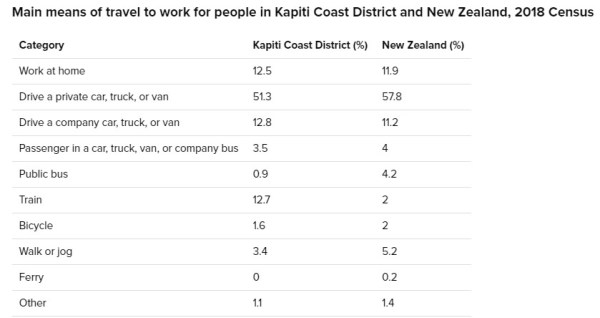

Kāpiti also has a high proportion of people using cars to travel to work. However, the train link to Wellington substantially lifts the proportion travelling by train. There is also a commuter bus service operating in the district but use is relatively low. Most rail commuters drive to the large car parks provided at the main stations. Cycling rates are low.

Transport accounts for 57% of Kāpiti’s gross greenhouse gas emissions. The largest segment, road transport, increased by 48% since 2001, while air travel is also important, at 9% of emissions and up 41% since 2001.

Public transport planning

Unlike Auckland, local authorities do not control public transport decisions. In Kāpiti, this is the role of Greater Wellington Regional Council. In Horowhenua it is Horizons. Further complicating this, the once-daily weekday Capital Connection train is outside the Metlink public transport system. Waiting at Paraparaumu station, no information comes up on the Metlink electronic board. Ticketing systems are also not integrated across the region.

In addition, the InterCity buses are outside this system. Gold cards allow free travel on one system but not the other. Waikanae retirees, wealthy or not, can travel all the way to Wellington for free, but the poor of Horowhenua get no similar benefits.

The Kāpiti Council does have control over local roads and could now be working hard to support cycling in the district. Through the motorway building, and the pro-active lobbying of the Kāpiti Council, there is a good spine of cycleways linking the towns. But where these intersect with local roads, cars have priority. On key points, cyclists

and walkers take their chances crossing roads. When lobbied to make these areas safe for adults and children cycling to school, council traffic engineers provide all sorts of reasons why they cannot do anything except put up signs.

In 2019 the Kāpiti Council declared a climate emergency. Since then the council has completed what they call a Sustainable Transport Strategy and a Long Term Plan. The former has no targets, no timelines and no strategy for decarbonising transport. It was adopted just days before the draft Climate Change Commission report was issued. The Long Term Plan has a continued and unquestioned emphasis on roading including building a new link road.

Spatial planning

At a time when we know that urban sprawl increases emissions and that we should also be protecting prime horticultural and agricultural land, the Wellington Regional Growth Framework favours greenfield. It suggests 15,500 new houses in greenfield developments and 10,400 new houses for existing urban areas within Horowhenua/Kāpiti in the next 30 years.

A prime example of this sprawl mentality can be seen in Levin. A 2,500-house development is planned which would be divided from the existing city by the as-yet unconsented Ōtaki-to-North-Levin expressway. Intentionally dividing a new community by a non-existent expressway would surely be something new in the annals of planning. Many of the new residents will be wanting to commute 94 km to Wellington or 50 km to Palmerston North.

What are the government and local authorities doing to reduce emissions?

The evidence to date is, very little. We await the reaction of the government to the final Climate Change Commission report. While many of us argue that the report is not ambitious enough, even their modest recommendations on transport put them at odds with the developments in the region.

Like other transport plans around the country, Wellington’s Regional Land Transport Plan is good on fine words and graphics but still directs the vast bulk of funding towards roads. It has a headline target of a 35% reduction in

transport emissions by 2030, to be achieved by reducing driving per person by 15-25% and an increase in active and public transport mode share from 28% to 39% of all trips. But the specific actions (“Ensure carbon emission reduction is a key objective underpinning regional transport planning and investment policies”,

“advocate for legislative changes”) are toothless and unmeasurable and are likely to be helpless in the face of concerted efforts to increase emissions in Kāpiti and Horowhenua.

Making a difference

Making a difference in this region will require visionary leadership and a total rethink and rewrite of most transport and urban planning documents. The government was bold in abandoning the Mill Road project in Auckland. The Ōtaki-to-North-Levin expressway project should also be stopped or greatly curtailed. Any new motorways should be heavily tolled.

All housing projects that involve sprawl would also be abandoned and instead there would be a focus on intensification, especially around transport hubs. This could include using the large park-and-ride areas to build apartments.

Kāpiti airport would be closed and high density housing built on the site. There is room for at least 3,000 dwellings on this site. The commute by bike along existing cycle tracks to a large public swimming pool, the main library, a primary school, Coastlands shopping centre and the station from the airport site would be about 10

minutes.

Given the topography and the series of small towns and villages, a visionary cycleway development program could tip the region into being a “Holland of the South”. Electric bikes are already becoming popular in Kāpiti, but given the low incomes in Horowhenua, incentives would be warranted. In addition, with the support of council

planners the series of villages along the coast could easily be developed into low traffic 15 minute neighbourhoods.

As discussed in the post Levin to Wellington, one EMU at a time, in terms of trains, the government is developing a business case for electrification of the line to Levin. Double tracking to Ōtaki could begin quickly.

Metlink is developing a case to improve train services between Palmerston North and Wellington and Masterton and Wellington. They already know it would require government funding, $300 million for the trains alone. But that is significantly less than the motorway to Levin.

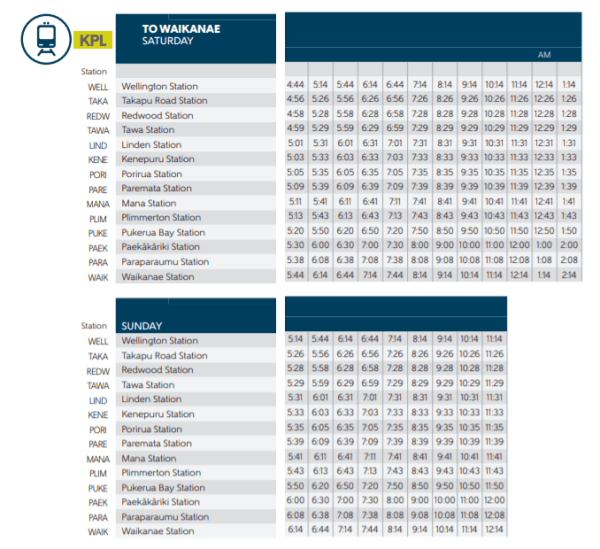

Current commuter trains from Waikanae would become more frequent. For example, the weekend evening services would increase from an hourly schedule after 7pm to every 20 minutes.

Trains would be able to carry more than three bikes. Fares would be affordable for families so instead of packing the bikes onto the twin cab ute the train would be a better option.

An overnight train would be re-instated linking Kāpiti and Horowhenua with areas to the north, providing a network effect with other train services.

The long-distance buses running through the district would be better integrated into the whole transport network. On- and off-bus amenities would be greatly improved.

Non-rail public transport would be improved. This is likely to involve a whole rethink about how the current bus network operates.

Driving to Wellington from anywhere along the coast would be discouraged by road pricing and restricted parking in Wellington.

Final thoughts

An article by Dave Hansford in the September 2021 NZ Geographic, “How to fix: Transport emissions”,

concludes:

'If we’re to hit our Paris target, we need to slash transport emissions across every mode. With sufficient political courage, some of those cuts could be made quickly: we could axe the fringe benefits perk on double-cab utes tomorrow, for instance. We could impose congestion charges, eliminate free car parking, and

prioritise unfettered right of way for buses and bicycles in commuter traffic. New road projects or housing developments could be consented conditional only upon the provision of walking, cycling and public transport facilities.'

If we’re to hit our Paris target, we need to slash transport emissions across every mode. With sufficient political courage, some of those cuts could be made quickly: we could axe the fringe benefits perk on double-cab utes tomorrow, for instance. We could impose congestion charges, eliminate free car parking, and prioritise unfettered right of way for buses and bicycles in commuter traffic. New road projects or housing developments could be consented conditional only upon the provision of walking, cycling and public transport facilities.

Unfortunately, bruised survivors of local transport battles know that that courage is often lacking. Dave’s earlier conclusion, that we will need to “crowbar New Zealanders out of their cars”, is closer to reality.

There are various lobby groups in Kāpiti concerned about climate change and working hard to present ideas to councils and the government on ways to decarbonise. These include Low Carbon Kāpiti, Kāpiti Climate Change Action Group, and Kāpiti Cycling. We are not short of ideas. We are short of politicians and planners with will, vision and courage to make the joined up decisions that will lead to liveable and sustainable communities.

All regions of Aotearoa New Zealand need to abandon plans for sprawl and highway building. We need quality transport and land use planning that supports the urgent decarbonisation of the transport sector.

Dr Paul Callister is a senior associate at the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies. Paul’s current research centres on climate change policy with his main focus is on sustainable transport.

Professor Robert McLachlan is an applied mathematician in the School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, and writes on climate & environment.

This article has been republished on publictransportforum.nz with permission from the original authors.